By Donor Father, Reg Green

The boy who received my son’s heart died Tuesday, although he wasn’t really a boy any longer. He was 37 years old. But when my 7-year old son, Nicholas, was shot in an attempted carjacking on a family vacation in Italy, Andrea Mongiardo was just 15.

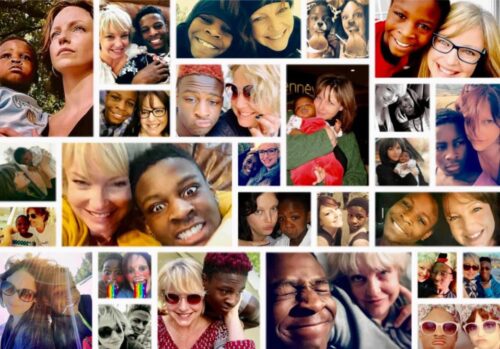

At the hospital in Sicily, my wife, Maggie, and I decided to donate Nicholas’ organs and corneas for transplant. They went to seven very sick Italians, four of them teenagers.

Andrea, who lived in Rome, had been in and out of hospitals because of a defective heart. Several operations had failed to help, and at the time of Nicholas’ death in 1994, he was receiving transfusions of blood products twice a week. In the words of his physician, Andrea was “struggling to survive.” His parents were in despair, knowing that a transplant was not only his best hope, it was his only hope.

In those days, the rate of organ donations in Italy was among the lowest in Western Europe. Andrea’s chances of getting a new heart in time to save his life were slim to none.

“We don’t feel as if Nicholas died all over again, as some doctors fear will happen to donor families. And, of course, we still have no regrets.”

Perhaps the most agonizing feature of being on a transplant waiting list is that patients can do nothing at all to influence if and when a new organ becomes available. Their future depends entirely on whether a family they have never met is willing to put its own mourning aside to help total strangers.

When Maggie and I were told that Nicholas had no brain activity, it was she who said, in her usual thoughtful way, “Shouldn’t we donate his organs?” We had no sense of what the outcome would be, who could be saved, what they would be like. But we realized we could squeeze some good from what was otherwise just a meaningless act of violence.

What we couldn’t have guessed was how much good: News of our decision spread like wildfire and so galvanized Italy that in the next 10 years organ donation rates there tripled, an increase no other country came close to. As a result, thousands of people are alive who would have died.

Some of Nicholas’ recipients were very close to death. One was a diabetic who was almost blind, couldn’t walk without help and was dependent on others. After receiving Nicholas’ pancreas cells, she moved into an apartment of her own for the first time in her life.

A 19-year-old got Nicholas’ liver. The day he died, she was in a coma. She bounced back to health, married her childhood sweetheart a year later, and a year after that they had a baby boy, whom they named Nicholas. He is now a tall, handsome young man with no trace of the liver weakness that has dogged his family.

Andrea took longer to heal. He had been sick for so long that his strength was undermined and, whereas the other six were soon back in circulation, he only slowly came back to full health. But when he did, it was for real. He got a job, played soccer, lived more normally than he had ever been able to growing up.

And that is how things stood until we got an email on Tuesday. “His heart was still functioning,” Andrea’s longtime doctor told us, “but the lungs were fibrotic because of drug toxicity related to chemotherapy treatment received three years ago after diagnosis of lymphoma. The final cause of death was respiratory failure.”

It was deflating, like the loss of a young nephew you never dreamed would go before you did. But we don’t feel as if Nicholas died all over again, as some doctors fear will happen to donor families. And, of course, we still have no regrets about the decision we took in 1994.

When the Italian media first asked Maggie how she felt about our son’s heart being transplanted into another boy’s chest, she said: “I always hoped Nicholas would have a long life. Now I hope his heart has a long life.”

Sadly, Nicholas’ heart didn’t reach old age. It did, however, perform nobly for three decades. I’m not surprised: I always knew it was pure gold.

For more information on Reg Green or Nicholas’ story please visit www.nicholasgreen.org.