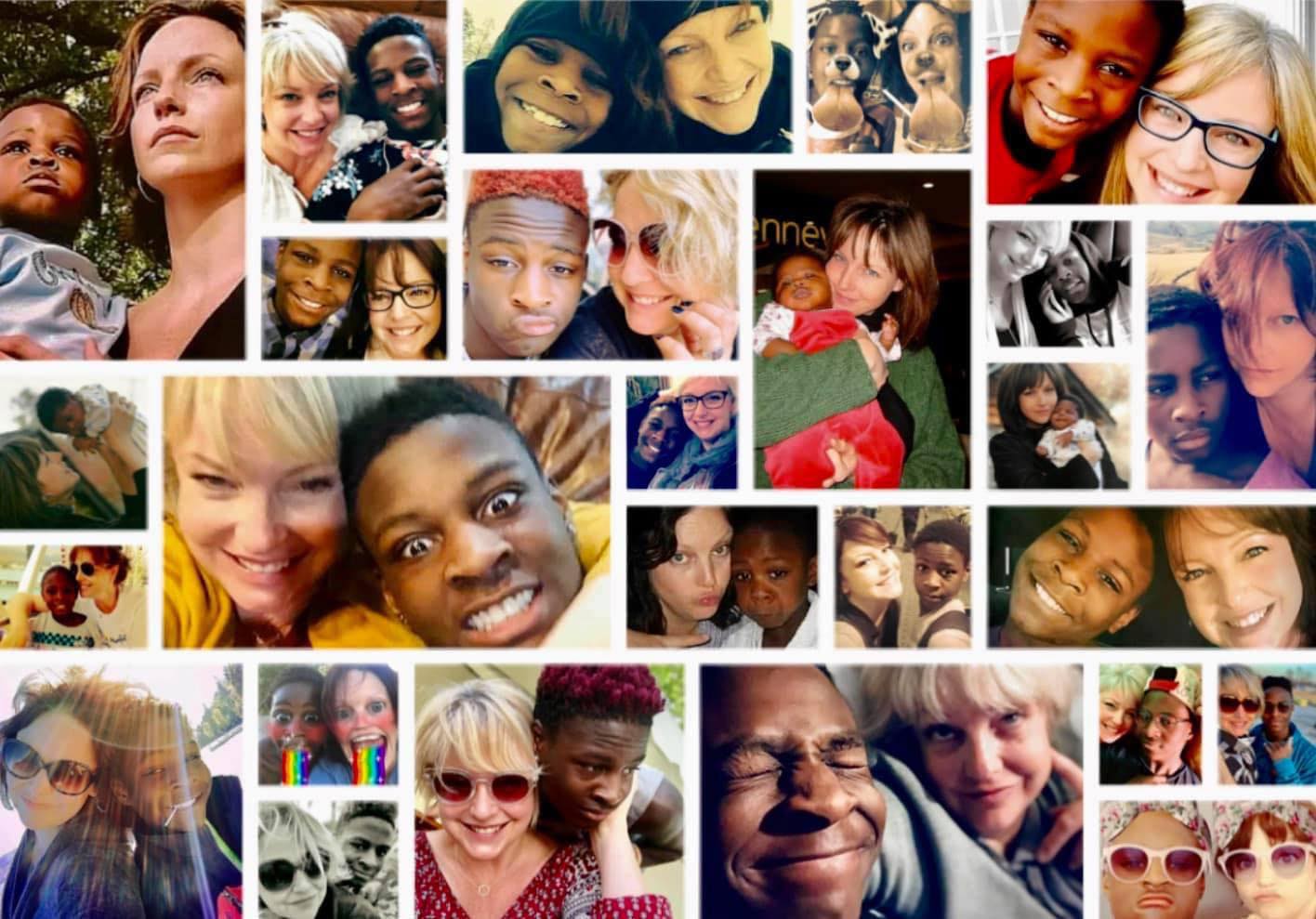

No one ever told me Ben wouldn’t wake up.

Not directly. Not with the kind of clarity a mother needs when she’s holding her child’s hand, watching the machines do what his body no longer could. I asked in a million different ways if there was a chance—not just for survival, but for the possibility of joy. It was a question they couldn’t answer. Maybe one they didn’t want to be responsible for answering.

I was explicit from the beginning that I was not a miracle person. The stakes were too high for miracles. I didn’t want my son to be kept alive in a body he would no longer recognize, just to keep his heart beating. I needed to know whether there was a real chance, not just for life, but for a life that included dignity, safety, meaning—and joy.

The injuries from the motorcycle accident were catastrophic. No one denied that. But no one brought up DNR should he code on the table during a surgery. And no one brought up organ donation. I had to ask for those things. Hospitals are places where preserving life is the primary focus. Quality of life is what I was thinking about.

In organ donation, there are two primary pathways for determining eligibility: one is brain death, where neurological criteria confirm the person has irreversibly lost all brain function. The other is DCD—donation after circulatory death. Ben never got a full brain death evaluation. His injuries were devastating, but because he was still intubated (a tube placed in the airway to assist in breathing), the final step in that process—an apnea test—couldn’t be completed in the traditional way. In the end, that’s what his extubation (the removal of his breathing tube) became. He took two breaths. And then he died in my arms.

Circulatory death is what happens after life support is withdrawn and the medical team waits for the heart to stop beating naturally. When it does—on its own, without intervention—the person is declared dead by circulatory criteria. Then, and only then, can donation begin. It’s a process grounded in both medical standards and deep respect for the natural course of death.

For me, circulatory death meant allowing my son a natural death when the possibility of meaningful recovery was statistically improbable and would have required many additional surgeries. It gave me time to prepare—to sing to him as he approached death, as I had when he was born. I was able to mother him one last time—and this time, it was to make his transition holy.

I chose DCD because I couldn’t bear the thought of him undergoing more procedures to preserve organ function at the expense of dignity. I chose it because nothing short of the possibility of joy would ever have been enough for my son. And when that was gone, I chose what I believe he would have wanted: to give what he could.

My son will never have children. He will never again walk into a room and light it up the way he used to. But he will be remembered. His name will be spoken with reverence by people he never met. Ben gave life. He restored sight. He lives on in the people he saved. And I know he would’ve been proud of that.

I support DCD because it gave Ben the chance to give something that mattered. Because I wanted his life—his name—and his story—to be remembered not just for how it ended, but for how much he gave, even at the end.

I chose DCD because one broken-hearted mother is enough.

Written by Eden Atwood, mother to Benjamin Atwood Anderson.