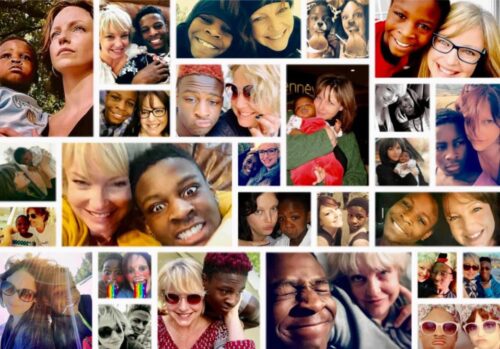

The couple shares their story to address the number one problem in transplantation: the gap between the demand for organ transplants and the supply of donated organs — especially in Black and African American communities.

Andre and Tessa Jones met in August of 2011. By December, at the age of 29, Andre was in the emergency room with kidney failure.

He had been sick for months — experiencing fatigue, nausea, back pain, high blood pressure — but these common symptoms were misdiagnosed by doctors.

“I wasn’t aware of what my symptoms really meant,” said Andre.

Andre would need a new kidney. Most of his family members had a history of high blood pressure, which precluded them from donating. After only a few months of dating, Tessa volunteered to be tested as a potential donor. She was a match.

“The first time I met his family was in the E.R.,” Tessa said, smiling. “But it was never a question. He needed a kidney, so I got tested.”

Andre spent 12 hours a week in dialysis. He needed the treatments to work and function, and to be healthy enough to endure a transplant. About a year after his emergency room visit, Andre and Tessa underwent surgery.

Andre was nervous but excited. Tessa felt calm and at ease, knowing that Andre could finally be healthy.

“We had friends fly in, both of our families came together and waited in the hospital for us, many meeting for the first time,” said Tessa. “They were there for one common goal — for Andre to get his life back.”

With a healthy kidney, Andre didn’t need to spend hours at the dialysis clinic each week. Andre was overjoyed to have the energy to pursue his passion of coaching young athletes, taking spontaneous trips, which wasn’t possible on dialysis, and eventually, marrying Tessa.

Unfortunately for Andre, this wasn’t the end of his battle. After four healthy years, Andre’s body rejected his transplanted kidney. He resumed dialysis, but this time, he and Tessa advocated for an in-home treatment option.

“As a young person, in-center treatment was depressing for him,” said Tessa. “Being able to do it at home is a mental break despite how tough it is to be sick.”

Being an advocate for your own healthcare is crucial. For the last five years, Dre has given himself dialysis treatments at home while he waits for a kidney donation from a deceased donor. His dialysis can be done overnight, and he can even travel, but it’s still not easy. Tessa gets up with him in the middle of the night, five nights a week to help.

“I couldn’t do this without her,” he said. “She’s been my nurse for like 10 years now.”

“This is normal for us,” said Tessa.

There is hope, though. Andre’s blood pressure is stable without medication, he’s able to remain active, and he’s working with transplant centers in both Washington and California to increase his likelihood of receiving a kidney transplant.

You can be that hope for someone like Andre. Register your decision to be an organ, eye and tissue donor at your local DMV or now on our website.

Black and African Americans are three times more likely than white Americans to have kidney failure.1 The need for donation and transplantation is more pronounced in multiethnic communities where disproportionately higher rates of diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease contribute to organ failure, especially kidney failure.

On average, African American and Black transplant candidates wait longer than non-Black transplant candidates for kidney, heart and lung transplants.2 These healthcare disparities are part of the need for education and outreach to help heal and save lives in our communities.

The waiting list currently stands at 106,669 with more than 60% of patients representing multicultural communities. According to our partners at the United Network for Organ Sharing, organ transplantation can be successful regardless of the ethnicity of the donor and recipient. However, transplant success rates increase if the donor and recipient share compatible blood types and tissue markers. Therefore, it’s vital that we expand the pool of donors, now and always, to ensure transplantation success for as many people as possible.

For more information on living kidney donation, visit kidney.org.

1National Kidney Foundation, as June 22, 2021, kidney.org

2SRTR Risk Adjustment Model Documentation: Waiting List Models, accessed June 23, 2021, https://www.srtr.org/reports-tools/waiting-list/